Supporting Inventors and Fresh, Creative Thinking

Coming in 2022, our Elf Inventor Awards support inventors and fresh, creative thinking. We’ll post more info over the course of the year. Learn more.

Coming in 2022, our Elf Inventor Awards support inventors and fresh, creative thinking. We’ll post more info over the course of the year. Learn more.

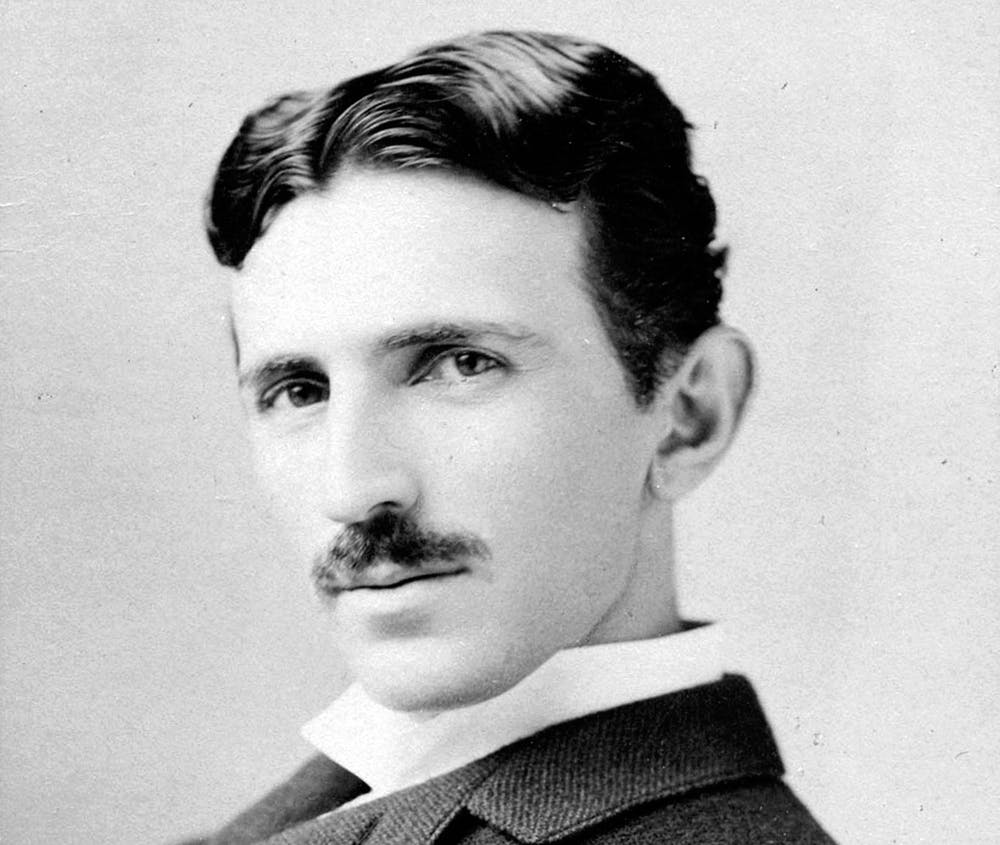

Born in 1856 in Smiljan, Croatia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Nikola Tesla was a Serbian-American engineer and physicist whose remarkable inventions would transform the way the world produced, transmitted and used electricity. Tesla’s father was a priest in the Serbian Orthodox church while his mother managed the family’s farm and was an inventor in her own right of household appliances. In 1863, Tesla’s brother Daniel was killed in a riding accident, which deeply affected the seven-year-old Tesla who was haunted by nightmares and troubling apparitions for many years after.

Tesla went on to study math and physics at the Technical University of Graz as a young man and later, philosophy at the University of Prague. In 1882, at the age of 26, while working as an electrical engineer with a telephone company in Budapest, Tesla came up with an idea for a brushless alternating current (AC) motor. While out on a walk, Tesla envisioned the idea for a brushless AC motor, marking out the initial concept along the sandy path he was walking on. He then rushed back to his office and drew the first sketches of electromagnets that he could see in his mind’s eye. He decided to move to Paris and got employed repairing direct current (DC) power plants for the Continental Edison Company.

Tesla knew his concept had merit and felt that he needed to show it to Thomas Edison, the famous inventor and engineer known for popularizing the incandescent light bulb. Tesla moved to the United States two years later. Arriving in New York in 1884, he went straight to the Manhattan headquarters of Thomas Edison’s business. Tesla got a job there and worked diligently. He impressed Edison by his hard work and also his ingenuity.

Seeing his employee’s creativity, Edison wagered Tesla that if Tesla could improve the design for his DC dynamos, he would give him $50,000. Tesla followed through, coming up with an excellent solution and solving the problem after several months of hard work and experimentation. Edison however, refused to pay up. Tesla realized it was time to quit and went out on his own.

Things were not easy for him, but he persisted. Tesla did not have the gigantic support of wealthy financiers such as J.P. Morgan who was determined to dominate the energy industry through his support of Thomas Edison’s DC technology. Tesla continued to work and struggled to support himself. He was granted over 30 patents for his inventions in just 1887 and 1888. When he was invited to address the American Institute of Electrical Engineers on his work, Tesla gave a lecture that drew the interest of George Westinghouse, an entrepreneur and engineer, with whom Tesla would collaborate with extensively in the next few years.

“If you want to find the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency and vibration.”

Invention often consists of improving on an existing idea and developing it in a focused way that leads to a tangible, useful result. Many of the inventions we attribute to one individual, are built upon the foundation of prior inventions and discoveries that made them possible. Inventions refine existing designs and prior work. They “stand upon the shoulders of giants” as Bernard of Chartres observed in the 12th century.

For example, the concept of alternating current was developed by the British physicist Michael Faraday. By 1832, the instrument maker Hippolyte Pixii from Paris, France, had built the first form of an alternating current electrical generator, using the principle of electromagnetic induction that Michael Faraday had discovered.

Tesla had studied alternating current (AC) in college and obtained an electrical engineering degree. Tesla’s great achievement lay in making an AC motor design that allowed the transmission of electrical energy along distribution lines in different directions in multiple ways, using the polyphase principle. Numerous contemporaries of Tesla had worked on methods of AC power distribution without any success.

When Tesla came up with the new AC design, his method challenged Edison’s existing electrical powerhouses that were built all along the Atlantic seaboard. Edison’s existing lamps that used direct current, were weak and inefficient. They also required high voltage levels to transmit across long distances, thus necessitating a direct current power station within every two miles!

Direct current flows in one direction continuously. This is useful for powering small devices like lamps and personal gadgets at home. However, this fails to work over long distances or for larger power supply needs. Alternating current changes direction 50-60 times per second and can be increased to high voltage levels without power loss while traversing long distances. The use of AC is clearly a better technology method for the transmission of power across long distances.

Alternating current became standard power in the twentieth century. Tesla’s inventions are in use in full force today. Electricity is generated, transmitted and converted to mechanical power by the methods that he invented. Tesla’s polyphase alternating current system, lights the entire world. This single, remarkable accomplishment literally changed the world!

Despite being a scientist and engineer, Tesla did not hesitate to look for higher inspiration beyond the quantifiable and physical. He relied upon his own powers of visualization and intuition. He valued his intuition and recognized its ability beyond logical deduction. Tesla took time to introspect, to pray and visualize daily.

“The gift of mental power comes from God, Divine Being, and if we concentrate our minds on that truth, we become in tune with this great power.”

Tesla knew that so much of the universe lies beyond our current knowledge and methods.

“The day science begins to study non-physical phenomena, it will make more progress in one decade than in all the previous centuries of its existence.”

He took the time to fully visualize ideas before working on them. Invention is a creative process. Invention involves creating in physical reality something which has only been dreamed of before.

“My method is different. I do not rush into actual work. When I get an idea, I start at once building it up in my imagination. I change the construction, make improvements, and operate the device entirely in my mind.”

Tesla had a penchant for the dramatic. Along with Westinghouse, Tesla lit up the Chicago Fair in 1893 with AC-powered electric lights, demonstrating irrevocably the magnificent power of electricity to visitors. It was a demonstration unlike anything else before it. At the time, streets were often dark and dimly lit at best at night. The spectacle of a brightly lit promenade, illuminating all buildings in the vicinity simultaneously, was amazing to behold.

Tesla helped illuminate more light bulbs at the Chicago Fair than available in the entire city of Chicago at the time. He also demonstrated an electric light that did not need any wires. His dazzling light display won people over instantly and also helped Tesla and Westinghouse to secure a government contract to generate electrical power at Niagara Falls at $150,000, besting the competition led by Edison and J.P. Morgan. Tesla and Westinghouse would go on to build the first large-scale AC power plant in the world.

AC electric lights lit up the night at the Chicago World’s Fair

Publicity photo of Nikola Tesla in his laboratory in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in December 1899. Tesla posed with his “magnifying transmitter,” which was capable of producing millions of volts of electricity. The discharge shown is 6.7 meters (22 feet) in length.

You have to experiment to discover new ways of doing things and to test out your ideas. Tesla conducted experiments constantly. In the 1890s, through his experiments, Tesla invented electric oscillators, meters, a high voltage transformer called the Tesla coil and more. He improved artificial lighting, experimented with X-rays and helped design remote control devices, wireless methods of communication and the radio.

When you experiment, you discover how to do things well. Along the way, you will make a lot of errors. Some ideas will be suitable to develop further, while others may be abandoned. With over 300 patents, Tesla invented and designed countless innovations that we use today. He pioneered the design of several technologies that power and light the world today such as alternating current (AC), electric induction motor, fluorescent bulbs and neon bulbs.

Here are just four of Tesla’s inventions - all breakthroughs!

Rotating Magnetic Field (1882): When a professor in Croatia told Tesla that it was impossible to create an AC-powered motor, Tesla was intrigued. He was confident that was not true and decided to figure out how to make one. He thought about it, going over ideas in his mind for two years. Then one day, the solution came to him when he was taking a walk. He realized that a rotating magnetic field would allow alternating current (AC) to power an engine before being converted to direct current (DC).

AC Motor (1883): Tesla retained these detailed plans for his AC motor in his mind without any written plans until he could build a physical model the following year. Tesla designed a new AC motor model. The alternating current created magnetic poles that reversed themselves on their own, without mechanical assistance like DC motors needed. The flowing AC current also made the armature, the revolving part of any electromechanical device, rotate around the motor, thus creating a rotating magnetic field that could be used as a motor. Tesla’s method of delivering power to residences and businesses via AC current overtook the ineffective DC power system promoted by his former employer, Thomas Edison. Today we receive AC power in our homes. Tesla’s method is still the primary method of powering electricity all over the world today.

Tesla coil (1891): The Tesla coil named after its inventor, used polyphase alternating currents to create a transformer that could produce high voltages with electric flames and crackling sparks. Today the Tesla coil is widely used for radio and television sets and for large electronic equipment.

Radio (1897): Tesla invented the antennas, tuners and many other aspects associated with radio, but unfortunately, his lab burned down in 1895, forcing him to restart and another inventor, Guglielmo Marconi supported by J.P. Morgan, was given actual credit for the wireless radio. In 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Tesla's patent had precedence but by that time, the world already had credited Marconi as the father of radio.

Image via Bettman, Getty Images

Photo of Mark Twain, a good friend of Nikola Tesla, holding Tesla’s experimental vacuum lamp in 1894

This lesson - a tough one for Tesla and one by omission - is to protect your work. Tesla, as we have shown partially here, was remarkably creative. He was undoubtedly inventive and a genius.

To be clear, an inventor’s job is to invent. It is not to be a marketer or a banker. Having those skills undoubtedly helps in pushing forward an idea or enterprise. Tesla was demonstrative and expressive, winning over audiences with his dramatic electrical displays and showing how his inventions worked.

Like many inventors, he was most interested in seeing his ideas come to fruition. He was focused on creating and building out his ideas. His name belongs among all the pioneers who spurred on electrical innovation. He was also generous.

Tesla’s innovations came at a time when the American landscape was dominated by a few major players, one of whom was J.P. Morgan. Morgan supported Thomas Edison’s work and had invested significantly in DC power. He was ruthless and determined to dominate industries and squash any competition.

Morgan demanded that Edison find a way to stop Tesla. At first, Edison tried to shoot down Tesla’s ideas as improbable. Then when Tesla won the support of industrialist George Westinghouse and began developing his AC motor fully and doing public demonstrations, Edison began an extensive smear campaign.

Tesla’s AC design work was supported by George Westinghouse, who had already invested in similar research with employees without success prior to Westinghouse hiring Tesla. Westinghouse financed the building of Tesla’s new AC motor and also his polyphase alternating current system. Westinghouse bought Tesla’s patents in return for a substantial royalty payment.

In 1893, Tesla successfully demonstrated his new technology at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, also called the Chicago Fair. He helped Westinghouse secure the government contract to design a new power station at Niagara Falls. Tesla designed the world’s first major hydroelectric plant for Westinghouse. With these two successes behind them, Westinghouse and Tesla were on route to becoming very wealthy. The government and the public supported their AC design.

J.P. Morgan was furious. He had also bid on the contract with Edison and lost out. He threatened to bankrupt Westinghouse. To help free Westinghouse, Tesla tore up his royalty contract, enabling Westinghouse to sell Tesla’s patents to J.P. Morgan. Tesla helped save Westinghouse from financial ruin, but lost the financial rewards of his own invention - something that would have made him one of the wealthiest men in the world.

In efforts to further discredit Tesla, J.P. Morgan and his supporters called Tesla a “dreamer” and incapable of commercializing his inventions. Dreaming though is a necessity when it comes to invention! An inventor is not a banker, a publicist, a marketing executive, an account representative or even a manufacturer. Despite all his influence, J.P. Morgan, did not have the skills or ability to invent like Tesla did, nor did the man that he hired, Thomas Edison.

“I don’t care they stole my idea. I care they don’t have any of their own.”

Sadly, while J.P. Morgan and Edison reaped the benefits of Tesla’s AC design, Tesla struggled financially to even support himself. Hence a lesson you can learn from his life is to protect your work. What’s easy to an inventor is not easy for the business magnate, financier or marketing executive. Protect your work so that you can support yourself, reap the benefits of your work and be free to keep creating.

Tesla featured on the cover of Time magazine on his 75th birthday

“That is the trouble with many inventors; they lack patience. They lack the willingness to work a thing out slowly and clearly and sharply in their mind so that they can actually ‘feel it work.’ They want to try their first idea right off; and the result is they use up lots of money and lots of good material, only to find eventually that they are working in the wrong direction. We all make mistakes, and it is better to make them before we begin.”

Tesla understood, better than most, the value of patience as an inventor. He persisted and worked on his ideas for weeks, months and years at a time.

While Tesla was often misunderstood, he did not let that deter his passion for pursuing his ideas or creating his inventions. He knew that people would often not accept his ideas, and that he had to be okay with that and keep going forward. Tesla thought at an accelerated rate. That was not something he ever needed to apologize for. At the same time, he was okay with accepting that he was alone and that many of his ideas were ahead of their time.

“Let the future tell the truth, and evaluate each one according to his work and accomplishments. The present is theirs; the future, for which I have really worked, is mine.”

“From childhood I was compelled to concentrate attention upon myself. This caused me much suffering, but to my present view, it was a blessing in disguise for it has taught me to appreciate the inestimable value of introspection in the preservation of life, as well as a means of achievement.”

It is important to have self-awareness and to take time for reflecting on yourself, your strengths and your weaknesses so that you can fully achieve your goals.

“When natural inclination develops into a passionate desire, one advances towards his goal in seven-league boots.”

Tesla knew the importance of solitude in providing him with insight, self-reflection, renewal and creativity.

“Be alone, that is the secret of invention; be alone, that is when ideas are born.”

While Tesla remained a bachelor during his life, he valued relationships deeply.

“Its not the love you make. It’s the love you give.”

“Invention is the most important part of man’s creative brain.”

Creating is essential to growth. Tesla recognized how invention and creativity transformed the world. He also reminds us to use our abilities to help make the world just a little better. With over 300 patents that included the world’s standard method for transmitting electricity and the radio, Tesla was one of the world’s most talented and exceptional inventors. He stands right alongside giants such as Gilbert, Coulomb, Watt, Volta, Oersted, Ampere, Ohm, Faraday, Henry, Gauss, Weber, Maxwell, Siemens, and Hertz. While he was not awarded a Nobel Prize though he richly deserved one, Tesla’s contribution was commemorated by having a unit of electrical and magnetic measurement named after him, like his intellectual peers. The Tesla (symbol T) is the SI derived unit used to measure magnetic fields.

Despite his inventions being stolen, being bullied and not reaping the financial rewards of his incredible achievements, Tesla did not give up and continued on. He was not motivated by greed and power like Thomas Edison who although talented, was so threatened by Tesla that he was willing to ruin Tesla’s career and life in the most ominous way. Edison attempted to demonstrate the risks of using AC current by killing a prison inmate through electrocution in an electric chair. Edison also killed numerous animals to prove his point. Edison did not want his influence to be usurped or to lose the backing of the wealthy and dominant financier, JP Morgan who was determined to dominate several American industries, in whatever means necessary.

Tesla, on the other hand, was not motivated by money. He considered creating and inventing part of his contribution to humanity. Tesla in many ways, was ahead of his time, as some of the power struggles that he faced then could be avoided today. He could have gained more financial backing and genuine support for his incredible inventions and ideas.

“An inventor’s endeavor is essentially lifesaving. Whether he harnesses forces, improves devices, or provides new comforts and conveniences, he is adding to the safety of our existence.”

Sources:

Kosanovic, Bogdan R., "Nikola Tesla." University of Pittsburgh, December 29, 2000. www.neuronet.pitt.edu/~bogdan/tesla/

O’Neill, John J. Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla. Cosimo Classics, 2007; originally published 1944.

Uth, Robert, "Tesla: Master of Lightning." New Voyage Communications, 2000. www.pbs.org/tesla/

Tesla, Nikola. My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla. Waking Lion Press, 2006; originally published as a series of articles in Electrical Experimental magazine, 1919.

In March 2017, Howard Head, the founder of Head Ski, was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his ski and tennis racket inventions. Howard’s journey however, into becoming an excellent skier was anything but smooth.

In the winter of 1947, Howard Head was taking a train from Stowe, Vermont back to his home in Baltimore, Maryland with some friends. He had just tried skiing for the first time and was shocked at how bad he was at the sport. Head was a tall man at 6 foot 4 inches. He struggled with skiing and later described his experience as humiliating and awful. He kept crashing and hurt himself numerous times. Every time, he tried to do a snowplow, he ended up face first in the snow. He could not believe how hard it was for him to learn the sport.

He realized though that some of his clumsy efforts at skiing were perhaps due to the skis themselves. The skis were made of wood and were long, heavy and clumsy. Head blamed the skis that he used for some of his skiing troubles and decided that he needed to build new skis out of a different material. His line of thinking was that a better design using lightweight aircraft materials would transform skis and make them easier to maneuver and a better skiing experience for anyone, from amateurs like himself to competitive skiing professionals.

"If wood were the best material, they'd still be making airplanes out of wood," Head said.

On the train ride back to Baltimore, Head began to sketch out his rough idea on a napkin. The 32-year-old engineer thought that he could design better skis built out of aircraft aluminum and plastic.

An aeronautical engineer by trade at the Glenn L. Martin Company, where he designed and built planes during World War II, Head had graduated from Harvard in 1936 with a degree in engineering sciences. Head persisted in his efforts and three years later, he launched his first product, a new metal ski with a revolutionary design under a new company, Head. Head Skis changed skiing forever. The new skis were lighter, easier to turn and more durable. The ease of use made skiing more accessible for new skiers. Head was so successful that the company’s skis dominated the growing ski manufacturing market, contributing almost half of all skis across the country for the next 20 years.

Here are four powerful lessons we can learn from Howard Head’s creativity and inventions.

Image via Head

“With both my skis and my racket I was inventing not to just make money, but to help me. I invent when it’s something I really want. The need has to grow in your gut. People who go around trying to invent something generally fall on their tails. The best inventions come from people who are deeply involved in trying to solve a problem.”

It is important to work on ideas that you are fully invested in; that are specific; and that you care so much about that you are willing to troubleshoot and figure out necessary details carefully.

Engineering draws upon science and mathematics to design new solutions, whether they are devices or systems. However, engineering progresses through the efforts of individuals who have a strong personal motivation to achieve a solution. This motivation can inspire an individual to acquire necessary analytical skills and engineering precision in order to fulfill a desired vision. Passion can lead to the most innovative results.

Born in 1914 in Philadelphia, Howard Head had a keen interest in literature and poetry. He went to Harvard University to study English and struggled for two years, but discovered that he was not a good writer. He worked as a copy boy and for newsreels but was unhappy with his performance and the jobs he took. Unsure of what to do next, Head went to a career counselor who encouraged him to take career tests to determine the right vocation. He took an aptitude test where he scored perfectly on the test for structural visualization or the process of imagining machines in three dimensions. He decided to pursue an engineering degree instead. After graduation, Head went on to work at the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company in Baltimore, Maryland where he built and designed B-26 attack bombers and PBM-3 flying boats. He started out as a riveter and then became an aeronautical engineer during World War II. At Martin, he also designed the B-26 Marauder, a twin-engine bomber. The exterior of the B-26 Marauder was an aluminum alloy sandwich wrapped around a honeycomb structure. It was the first WWII aircraft to use plastic on a large scale. Head would use this experience to build his skis.

Head knew what he was good at and what he did not do well, even if it was a subject he enjoyed. Self-awareness is key to achievement.

Image via Head

Image via Head

“If I had been a dedicated skier when I went to Stowe, I probably would’ve accepted as gospel the idea that skis had to be of wood. But as a novice, I thought wooden skis were crude.”

When Head did not enjoy his ski vacation because he could not easily maneuver the heavy wooden skis that he had, he decided to build his own, using different lighter materials. People were skeptical of his ideas and he faced numerous design setbacks but he kept going. He persisted and did not give up.

He took the $6,000 that he had won from playing poker and rented a small section of an electrical appliance shop from Albert Gunther Inc in an alley off of Biddle Street in Baltimore, Maryland. Head then scrounged aluminum scraps at Martin Aircraft. He quit his job and got to work building his first prototype for a flexible laminated ski. He convinced three mechanics from Martin Aircraft to work with him during the evenings and weekends. They built not only the skis, but the equipment to build the skis. Together, Head and his production team built six pairs of skis that first year. The skis were essentially metal sandwiches — two layers of aluminum with plywood sidewalls around a plastic honeycomb core.

Head used structural principles from the aircraft industry and new lighter materials to build better ski equipment. His efforts revolutionized the ski industry, taking it out of the hands of wood crafters and placing it squarely in the domain of scientists and engineers.

Head rushed back to Stowe, Vermont during Christmas time in 1948 to show his skis to ski instructors. Six of the seven pairs that Head brought to demo, broke just as the instructors flexed them with their hands. Head skied on the last pair and then it broke.

One of the Stowe instructors, Neil Robinson, encouraged Head and offered to keep testing his new ski creations. That positive reinforcement was enough to keep Head at it. Head did not give up. Head kept designing new skis and sending them to Robinson, who would test them and then send them back when they broke. Head was able to see all the flaws in his designs and to keep improving. By the end of the first winter, Head was able to create skis that were half as heavy but equally strong as the traditional wooden pairs in use. He built 39 more versions in the next two years. They all broke.

“Every time one of them broke, something inside me snapped with it.”

Despite the repeated failures, Head refused to give up. He ran out of money and turned to his friends for support, borrowing cash to continue his venture. His persistence convinced his production team to stay on even when he could not pay them. After three years of failure, Head was almost ready to give up. He was living in a basement apartment for $20 a month. He had not paid his crew for a year and a half, and he was washing his dishes in his bathtub. He realized that he had to make it work or quit and get another job. Head persisted and in the spring of 1950, he showed up at Tuckerman's Ravine in New Hampshire and asked 10th Mountain Division veteran, Clif Taylor, who had tested prior versions for Head, to try out some new skis.

Taylor did and to their mutual excitement, the new skis worked in every conceivable snow condition!

It took Head three years since that fateful trip to Stowe, Vermont, but in 1950, he figured it out. He designed and built the Head Standard, a flexible ski made of metal, plastic and plywood that was three times more flexible than wooden skis and could turn easily in any ski condition.

“If I had known then that it would take 40 versions before the ski was any good, I might have given it up. But, fortunately, you get trapped into thinking the next design will be it.”

Head traveled across the country selling his new skis out of his station wagon at ski resorts and parking lots. The skis sold quickly. At first, people were skeptical and labeled them ‘cheaters’ as they made turning so much easier. Head Skis were selling like hotcakes in Colorado and New England, with ski instructors encouraging new students to only ski with the new equipment!

Image via Head

Head’s new ski revolutionized the sport. By 1966, the Head Ski Company employed 500 people, was selling 300,000 skis a year in 17 countries and earning $25 million annually. Soon enough, Head Skis were in use by Olympic skiers both in the United States and Europe, dominating competition at the 1964 and 1968 Winter Olympics. At the 1964 Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria, Billy Kidd from Steamboat, Colorado became the first American man to win an alpine skiing medal. He won a silver medal in the slalom on Head skis.

Howard Head had succeeded in revolutionizing the ski industry, encouraging new people to try out the sport, making skiing easier overall and helping people become better skiers.

“In the long run, it’s the details that make ideas work.”

Image via Head

![Patent diagrams comparing the “sweet spots” in Head’s tennis racket [5A] and a traditional racket [5B]. The “sweet spot” in Head’s racket is labelled zones 33, 35, 37 which are significantly larger in area than the corresponding zones 33’, 35’, and …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54bdcba5e4b08f92b173441f/1549822432194-NVWVA0MFE9C9ZHIBBAFE/HeadRacketPatent.png)

Patent diagrams comparing the “sweet spots” in Head’s tennis racket [5A] and a traditional racket [5B]. The “sweet spot” in Head’s racket is labelled zones 33, 35, 37 which are significantly larger in area than the corresponding zones 33’, 35’, and 37’ in the traditional racket. Howard Head, “Tennis Racket,” US Patent 3,999,756 (filed 10 Sept. 1975, granted 28 Dec. 1976).

Pam Shriver playing with a Prince racket during a semi-final match against Martina Navratilova at the U.S Open Tennis Championship, September, 1978. The sixteen-year-old Shriver upset the number-one seeded Navratilova to become the youngest finalist ever in the U.S Open Tennis Championship. (AP Photo/Dave Pickoff)

Head could have sat on his laurels. He had achieved a lot and his business was thriving. However, he chose to keep going and using his inventive mind to create a new, oversized tennis racket. Just like his start in designing skis, Head became motivated to create a new tennis racket based on his own tennis playing experience.

In 1971, Head sold his business to AMF for $16 million, explaining that the company had grown beyond his ability to manage it. He took up tennis in retirement at the age of 60 and built a court underground at his home. He spent a lot of money and effort into learning how to play tennis. He did not improve though the way that he had hoped. Head purchased a Prince ball machine to practice playing tennis. He redesigned the machine and invested in the company, patenting the improvements that he had made. His tennis playing however did not improve!

Out of the blue, he had an idea to make the tennis racket bigger and so he did. The process took him two years and he constructed a tennis racket that was 20 percent wider than the old wooden rackets, one inch on each side. This in turn, gave the racket a 40 percent larger “sweet spot.” A sweet spot is the optimum place on a racket face for impact with the ball. Just like he had replaced wood in skis with a lighter material, Head substituted aluminum into the tennis racket’s wooden frame. Later, he used graphite. Prince sold the new tennis racket in 1976.

Similar to the resistance that Head encountered when he introduced his metal skis, he faced snickers and derision with his new larger tennis racket, that many called a “snowshoe” racket. The new Prince Classic, as the tennis racket was called, nonetheless, became an instant hit with tennis players.

Head successfully improved upon an existing product to enhance performance. As tennis player Pam Shriver demonstrated in 1978, the new racket design was a tremendous success. Within four years of the product’s launch, over 700,000 tennis players around the world were using it.

In two years, Prince Manufacturing controlled 30 percent of the U.S. market, 25 percent of the global market and dominated global racket sales. Howard Head, the tennis newbie, who could not play tennis well, had turned out to be one of the industry’s biggest innovators.

A consummate entrepreneur, Head received a royalty payment on every Prince racket sold. He sold the company to Chesebrough-Ponds for $62 million in 1982.

Howard Head kept on playing tennis and skiing down mountains for the rest of his life. Head got married to Martha Fritzler who shared his love of skiing and settled in Vail. Head went on to launch the Howard Head Sports Medicine Center to help athletes in 1987 and also supported numerous other causes. He was inducted into the Colorado Ski and Snowboard Museum Hall of Fame in 1990 at the age of 75, a year before he passed away. Head is remembered to this day with fondness at the ski slopes he frequented in Aspen and Vail, Colorado. His two inventions - the metal ski and oversized tennis racket - are on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institute with the inscription praising Head as the "patron saint of average athletes."

Howard Head's quotes in this story are taken from stories previously published by the Vail Daily, the Vail Trail, the Colorado Ski and Snowboard Museum Hall of Fame, Sports Illustrated (Sept. 29, 1980) and Airport Journal "A Bad Skier's Revenge," (Nov. 5, 2005).

View prior profiles by searching for Profiles. Read our Profile on U.S. Skiers and Snowboarders at the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics. Learn more about our Elf Ski app that we’re developing that helps skiers and snowboarders track their workouts and improve performance.